Reading: Time Frames by Scott McCloud, New Media Reader.

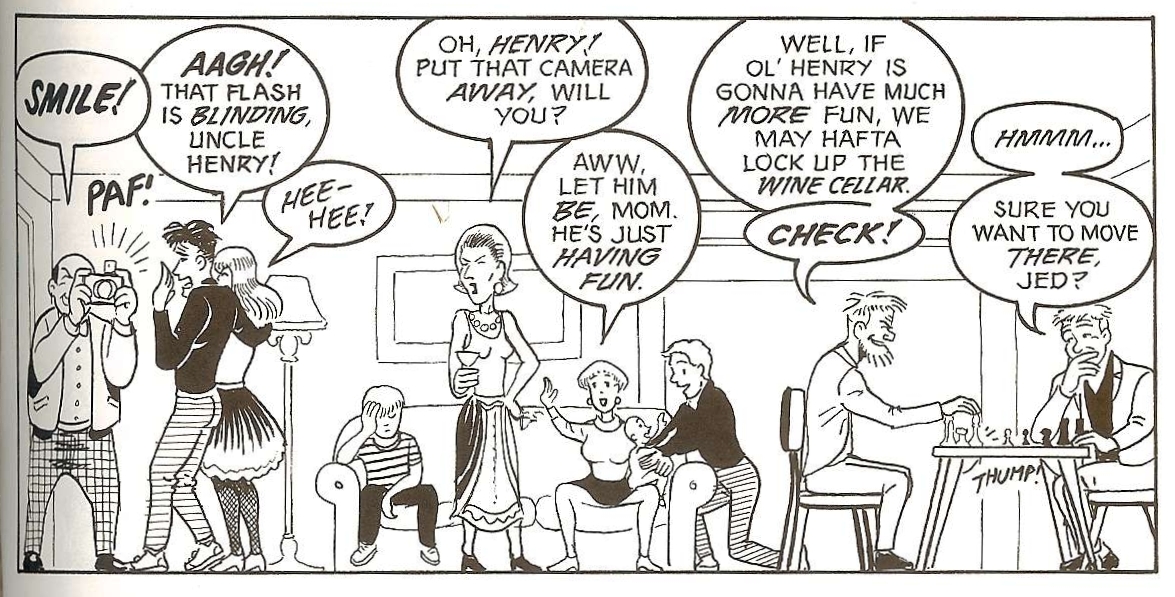

This reading was a great finale to Virginia Tech’s New Media Seminar. McCloud’s dissection of time and space in comics is fantastic! Take a look at the image below – is it one point in time, or are there a sequence of points? Are you aware of this when you are reading the comic?

From this blog.

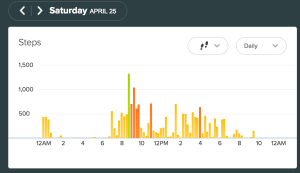

This week we were asked to think about how time is encoded in some other medium or technology. I happened to be staring at my Fitbit log, so let’s think about how Fitbit considers time. Here is a screenshot of my Fitbit Dashboard from the weekend.

You can click through the days using the arrow tabs on the left and right – in this way, time is depicted as pages in a book. Each page is one day (12:00 AM to 11:59 PM), divided into 15 minute increments. However, there’s another aspect of time: clicking on the “Daily” dropdown you can get a 7-day panel:

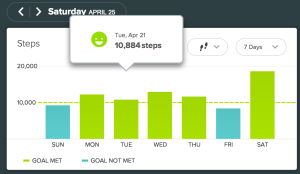

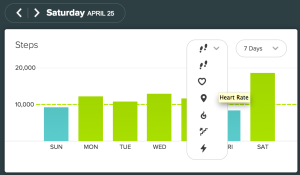

Time looks different now. Each bar represents 24 hours. Further, you can select different types of information to view: steps, heart rate, calories, etc.

Fitbit (and other activity/calories/diet logging systems) tend to think of time in a similar way:

- A day is from 12AM to 11:59PM. Not when you wake up and when you go to bed; not from noon to noon.

- When you consider a different length of time (e.g., a week instead of a day), you tend to get a different representation of the data. You can only see one panel at a time, one “page” in your time book.

- Time is associated with wins and failures. You see smiley faces and gold stars during time frames where you met your goals. You can visually tell your “bad” days from your “good” ones. I played in an ultimate tournament on Saturday, so it was a decidedly “good” Fitbit day.